Inside the Yema Manufacture: The Journey of an In-House Calibre

Whenever you read about high-end watchmakers and their watches, there is often one term that just keeps coming back: Manufacture Calibre. Despite having a fairly good understanding of both what this means for the watch, and it is price tag, I realised that I had very little idea about what this meant when it actually comes to the manufacturing process. So, when Yema asked if I would like to visit their manufacture, I jumped at the opportunity to discover how you actually make a manufacture calibre. In depths of December, I set off early one morning to Morteau, the home of French watchmaking, and also the home of Yema. Yes, the town might rather quiet and quite sleepy. However, with just a short drive around the area, you really come to understand the significance, both historical and strategic, of this location. One of things that struck me as I entered their facility was how un-industrial it felt. I have certainly visited many friends’ apartments that felt more like a factory than this.

Before diving into the technical details, I think it would be useful to briefly cover Yema’s history. Founded in 1948 by Henri-Louis Belmont, the brand quickly gained notoriety for its tool watches, something that the brand is still famous for. They grew their operation incredibly rapidly, to such an extent that in the 1960s they were considered to be one of the most significant French exporters of timepieces. Yema watches could be found absolutely everywhere, from the wrists of adventurers and soldiers to the wrists of Mario Andretti (who won the Indy 500 in 1969 wearing a Yema) and Jean-Loup Chrétien, the first French astronaut in 1982. For a brief period in the 1980s, the brand was led by none other than Richard Mille, the very same person behind the watchmaker that carries his name. After his exit, Yema went through a difficult period under the ownership of Seiko. By the early 2000s, Yema was a far cry from the industry-leading brand it once was.

This is where the story starts for the Yema that we know today. Their vision was clear: bring Yema back to the forefront of independent French watchmaking. This materialized with their first generation of manufacture calibers. But Yema wanted to go further. In 2020, they released their second generation of in-house movements, the Yema 3000s. Yet again, they wanted to go further. Much further. So, in 2023, they released their latest and greatest calibers, entirely designed by their team and manufactured exclusively for them. This generation of movements is known as the Caliber Manufacture Morteau, or CMM, and breaks down into a series of impressive complications that have taken the watch world by storm. Now that you are caught up on the history, let us take a look at how they are made.

Like any good design project, the Yema CMM calibers start as a series of drawings, models, and plans on a PC monitor. In most watchmakers’ headquarters, the designers would either be squirreled away in their own little corner of the offices, looking for some peace and quiet to get on with the hard work. This is not the case for Yema. The design team’s office neighbors the main CNC machining facility and quality control room. Why is this significant? Well, this allows the manufacturing team to catch errors and issues, bringing them straight back to the designers who can start working on a fix immediately. Speaking to some of the technicians during the visit, they recounted a time when they were able to identify, fix, and manufacture a solution to a problem on a bridge in just under an hour. If they were at a bigger brand or working with off-site suppliers, this issue would have taken days, if not weeks, to solve. And maybe that just gives you a little hint as to why Yema’s watches are so fantastic: they can do ten times the work on their own compared to working with others.

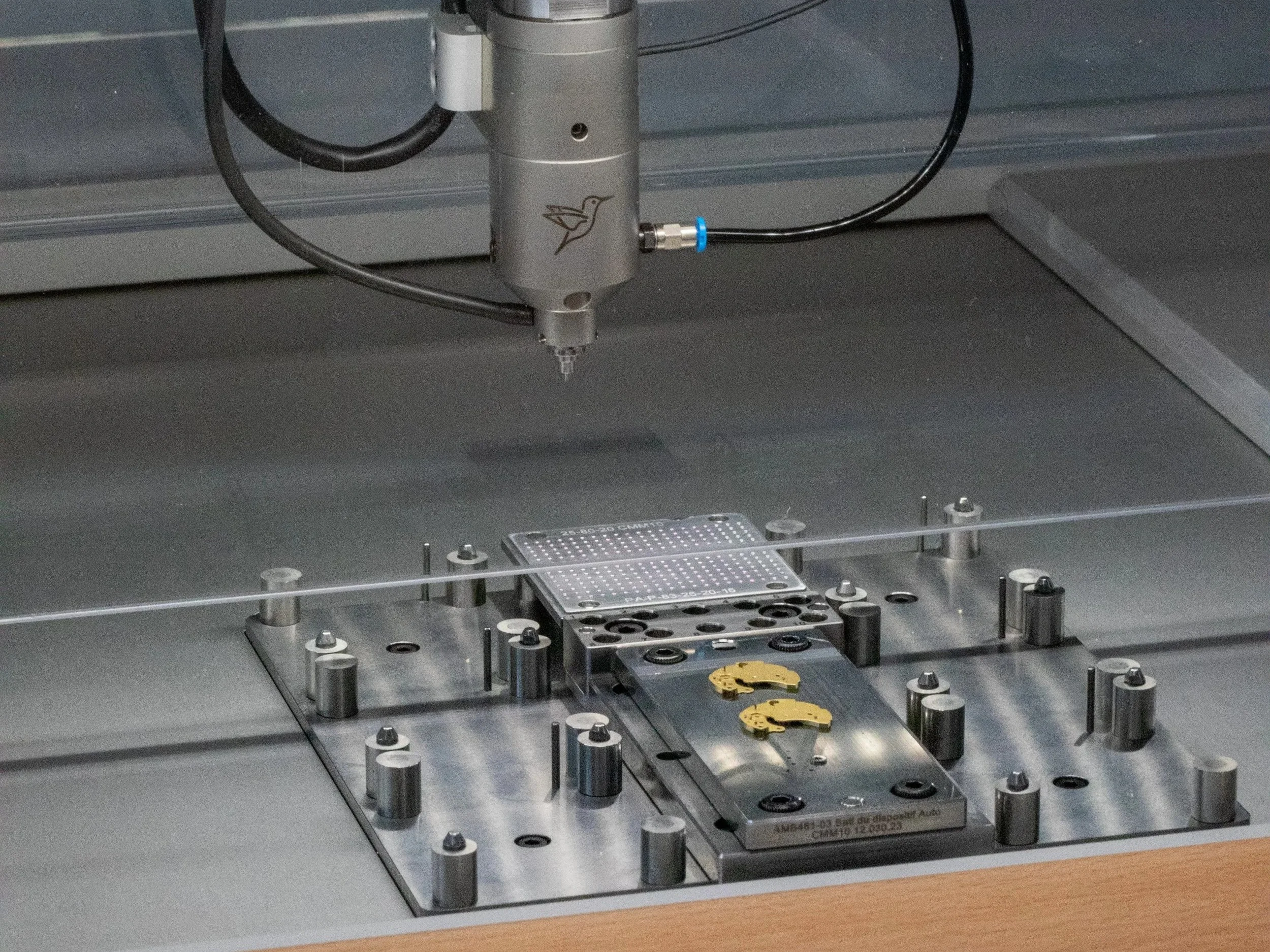

Speaking of accomplishing herculean volumes of work in a short amount of time, one area of the production process that I think merits a spotlight is their CNC machining facility. Equipped with a fully custom automatic 5-axis robot (yes, that is a bit of a mouthful of technical jargon), Yema can run their machine 24 hours a day, 7 days a week without having to stop. It barely even requires human input: technicians just have to set it up for the specific caliber bridges or plates that they want to manufacture and then they are away. The only other human input required once it is running is the refilling of the brass blanks. They do not even have to stop the machine to do that. The CNC facility could genuinely go on forever. Certainly, this is a useful capacity to have if you are trying to grow production.

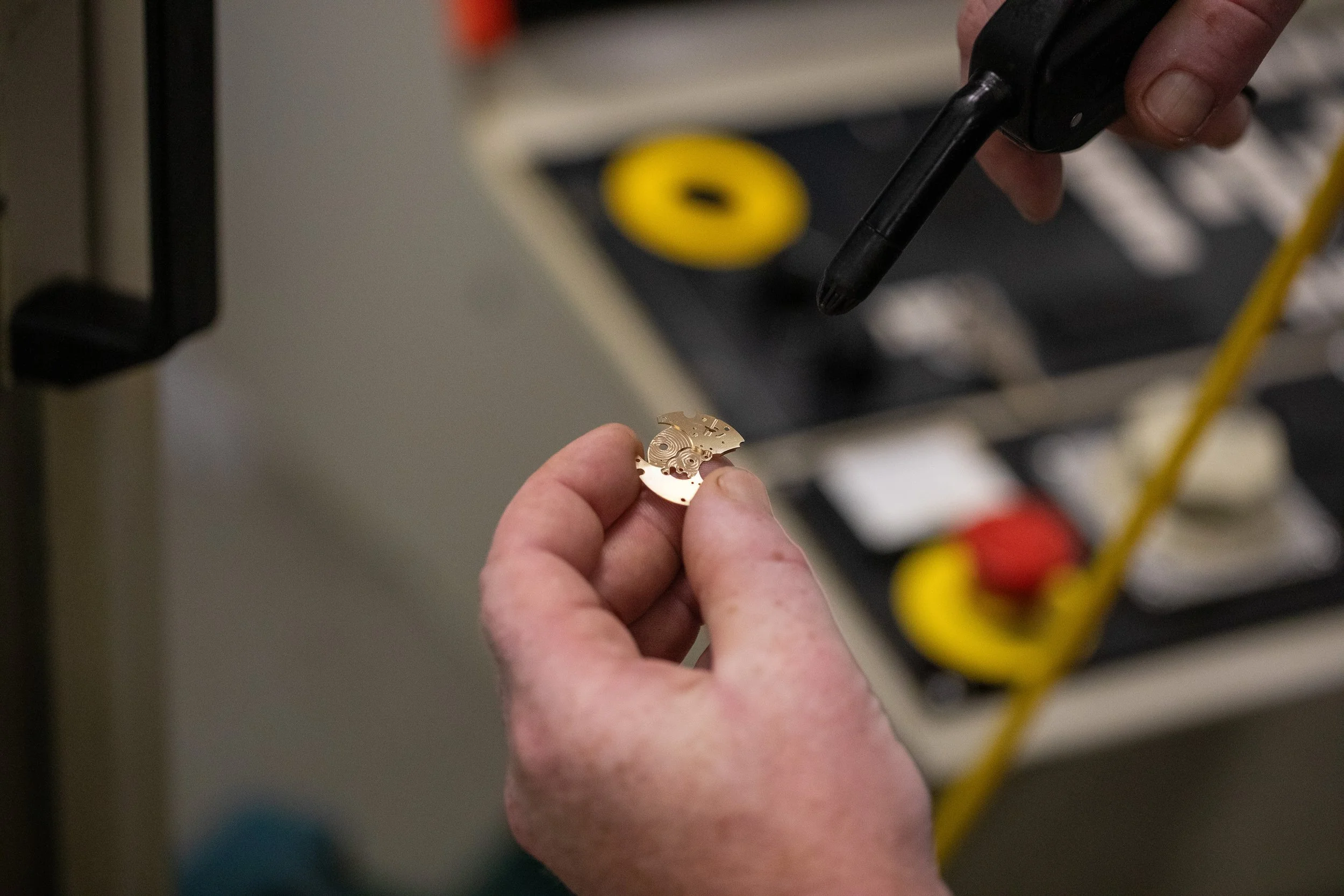

Just next door to the CNC room was another impressive high-tech room that blew me away: the jewel-setting and QC room. This is where all the calibers get fitted with their synthetic rubies. In many manufactures, the setting of the stones is done manually. But not chez Yema…they have automated the system with a very fancy state-of-the-art machine. This was probably my favorite part of the process to watch. It is almost inconceivable that a machine hooked up to a computer program has the ability to effortlessly execute delicate and precise movements in a carefully orchestrated sequence. This is also the moment when technicians are able to properly check the bridges and plates for any defects before they are unfixable.

Once the bridges and baseplates have been machined and fitted with their jewels, they actually leave the Yema factory and cross the border into Switzerland, where they undergo treatment, which for Yema is either a svelte anodized coating or a sunray finishing. The components are swiftly sent back to the manufacture, along with a host of other pieces like the escapement and gear train, which Yema sources from suppliers. At this stage in the growth of their manufacture calibers, it is completely unrealistic to expect that they have the capacity to manufacture such specialist parts. Strictly speaking, very few brands actually have the ability to produce their own escapements and hairsprings.

Back in the manufacture, all the components are sent straight up to the storeroom. When you think of what a storeroom might look like in a factory, you probably think of a giant Costco-like warehouse with pallets, forklifts, and employees in hi-vis walking about. Rather obviously, this is not the case in a watch factory. The reality is much closer to an archive: quiet, clean, and carefully arranged with thousands of small trays. Walking through the aisles was much like being in a candy shop: in every tray was something different, finished micro-rotor movements in one, escapements in another, and a finished tourbillon watch in the next. The technicians responsible for this part of the manufacture are tasked with assembling “kits” for the watchmakers. This means preparing batches of unassembled calibers from a list of parts, ready to be taken up to the room where the magic happens.

The assembly room was nothing quite like anything I had ever seen before. Not in the sense that it did not look like a watchmaker’s workshop, but in the sense of energy and concentration pooling in a single place. Watchmaking is definitely a profession that we associate by default with years of experience and training. You can imagine my surprise when no one in the room looked too much older than me. Definitely a shock, when I am often a good ten or so years younger than most people I meet in the industry.

The other thing that really surprised me was the speed at which the watchmakers were working. There was no haste or rush, just efficiency. Again, watchmaking has this stereotype of being a slow-moving line of work. One of the big reasons the watchmakers are able to work at such a rate is the preparation work that happens in the storeroom. As a result of the kits that are pre-prepared for them, the watchmakers are able to work on up to 25 calibers simultaneously, executing the installation of each component with ease. The quiet hum of the machinery and flawless handiwork of the watchmakers was mesmerizing to watch, and it was fascinating to see the calibers come to life through the addition of each new component. It was almost like watching life slowly being breathed into the movements. This workshop is also where the watches are tested and put into their cases, turning them into the final product that we know and love.

Thinking about the whole process from a big-picture view, I think it is impressive and almost poetic that a watch is designed, manufactured, and assembled all within the confines of a space not too much bigger than a large family home. Aside from a brief foray just 15 to 20 miles away for some finishing, the watch’s lifespan can be pinpointed to a single journey of around 50 yards. I find the fact that Yema produced around 40,000 watches that have more or less all taken this specific path through such a small space very special. Thus far, I have spent a fair amount of time talking about the technology, machinery, and processes that go into making these watches, and maybe not enough time talking about the 38 people behind the whole operation, each ensuring that the watches they produce are delivered to an exceptionally high standard. I think part of Yema’s secret sauce is this proximity between the processes, the product, and the people. Every employee is within arm’s length of the production process, which probably reinforces the connection between the whole team and their watches. This all goes to show that despite all the wonderful innovation and technology that has been brought to watchmaking, at the end of the day watches are all about the story and human connections behind them.

Find out more about Yema, their Manufacture, and their watches here.