Grand Seiko Manufacture Tour in Japan

It has been a year since I traveled to Japan with Grand Seiko, and I am still processing the experience. This has been one of the hardest articles I have ever written. Not because I lack material, but because the trip was so meaningful that putting it into words has felt almost impossible. It combined everything I love about watches, history, design, technical mastery, and culture, with moments that touched me personally in ways I hadn’t expected. I was so moved by the trip that I am already planning my return, this time for pleasure, in just a few weeks.

Even before I set foot in a watchmaking studio, the journey carried a sense of occasion. I flew to Japan on my birthday. Because of the time change when crossing the International Date Line, that birthday was effectively cut short. At the time it felt like a sacrifice, but I couldn’t have asked for a better reason. When I finally arrived in Tokyo in the late afternoon, tired but buzzing with anticipation, I checked into my hotel room to find that the Grand Seiko team had arranged a cake to celebrate my birthday. It was a small gesture, but it meant everything. It set the tone for the days to come: this trip was not just about watches, but about people and hospitality. Later in the week, during one of our group dinners, they presented me with a pair of chopsticks, simple, refined, and deeply Japanese, that remain one of my most cherished souvenirs.

First Days in Tokyo: Ginza, Wako, and a Sense of Place

Our group stayed in Ginza, Tokyo’s luxury district and one of the great centers of watch culture. The wide boulevards were lined with flagship stores and department stores, each one polished and carefully curated. It felt orderly and calm, even with the flow of people. The district had the air of an open-air gallery, with architecture that balanced modernity and tradition. Our hotel was just a short walk from some of the most important locations in Seiko’s history.

On the very first night, I joined a dinner where I met some familiar faces from the American press. It was a comforting way to start the week, a chance to shake off jet lag over drinks and swap stories about our flights before the formal program began. That dinner was the last moment that felt informal. From the next morning on, I was fully immersed in Grand Seiko’s world.

We began with a visit to the Wako flagship inside Seiko House Ginza. Wako’s clock tower is one of Tokyo’s most recognizable landmarks, standing at the corner of Ginza 4-chome like a symbol of Seiko’s presence in the district. Inside, the space was quiet and elegant, more like a gallery than a typical retail store. Later that day we visited Grand Seiko’s Omotesando boutique, a more contemporary space with a minimalist, architectural design language. Experiencing these two environments back-to-back, one deeply tied to history and the other focused on the future, was the perfect way to understand Grand Seiko’s dual identity.

Meeting the Mind Behind Kodo

One of the highlights of the Tokyo portion was spending time with Takuma Kawauchiya, the creator of the Kodo Constant‑Force Tourbillon. He recalled the skepticism he encountered when he began: “There was a notion… that a tourbillon is supposed to achieve high position and high accuracy. But in reality, there was thinking within the community that it actually did not affect or improve the accuracy of the watch so much.” His earliest work focused on the problem itself: “My first task… was to research on how to… improve accuracy of watchmaking. And… I really understood how the decrease in torque was the main… reason for accuracy to go lower… So to tackle the issue of gravity through the tourbillon and to tackle the issue of a decrease in torque with the constant force, the combination of that two… must be very important… And once I got that idea, I was obsessed…”

From the beginning, the concept wasn’t constrained by branding. Kawauchiya explained that “the concept was more of an open project… The objective was to simply create the ideal watch without any boundaries… After… the decision was made… to introduce this new mechanism as a Grand Seiko watch… we still wanted to… keep the skeletonized movement aesthetic… The important elements of the Grand Seiko design principle are very much reflected… in terms of the case design, hand design…”

When he presented the finished architecture, he put it simply: “Kodo integrates these two mechanisms on the same axis as one unit, which allows the torque generated by the constant force mechanism to be delivered to the balance without loss or fluctuation. This enables Kodo to achieve precision of amplitude fluctuation within plus or minus five degrees and rate fluctuation within plus or minus one second per day for over 50 hours…” Just as crucial was the feeling it creates: “Suppose art is an expression or a work that moves someone emotionally… the motion of a watch mechanism, or the sound produced by a mechanism, is also a form of artistic expression… We wanted to address two forms of artistic expressions, motion and sound.”

He then described the choreography on the dial: “In Kodo, the outer carriage with the constant force mechanism, wraps around the inner carriage, which is the tourbillon… The inner… rotates smoothly. The outer… moves intermittently, once per second. The coaxial rotation of these two differently moving carriages creates a unique visual effect… more stimulating than the perhaps monotonous motion of an ordinary tourbillon.” The acoustics were part of the composition: “The constant force mechanism creates an impulsive sound when the stop wheel and stop[p]er collide during its operation.” The choice of an eight‑beat balance was musical as well as technical: “The eight kickings per second, together with the impulse sound of the constant force mechanism at the rate of once per second, results in the rhythm known… as the 16th note feel…”

Synchronizing that rhythm demanded extreme precision. He noted, “For the watch to play the 16th note feel accurately, very high dimensional accuracy of the related components was required… the machining and eccentric tolerances… were made more than twice as tight as usual… We added a mechanism… to adjust the position of the stopper… The goal was to adjust the position of the stopper until Kodo achieved a perfect 16th note feel.” The energy budget was daunting: “Combining an eight vibration balance and the constant force mechanism requires more than five times the energy of a regular… watch…” and that forced clever materials choices: “I utilize ceramic as the material for the stop wheel, as it can withstand strong impact and friction… using a material like ceramic, which is difficult to machine… was a significant challenge.”

Asked about his path from guitarist to watchmaker, he answered with disarming candor: “My mother told me that you are very… good with fingers… She said, I think you… have more talent in a profession like watchmaking than as a musician.” And when someone wondered if the solitude of the bench had been hard after a more social life in music, his answer was brief and telling: “Not at all.”

Into the Mountains: Shinshu and the Soul of Spring Drive

After a few days in Tokyo, we boarded a bus and headed toward Nagano. The ride offered a different view of Japan: stretches of farmland, small towns, and mountain ranges gradually replaced the density of the city. It was a welcome change of pace, and our guide filled the time with background on the regions we passed and the history of Japan more broadly. By the time we reached Shiojiri, home to the Shinshu Watch Studio at Seiko Epson, the shift from the capital to the countryside felt complete.

The visit began with a technical session on Spring Drive’s origins. Development stretched back to the 1970s, with an early prototype completed in 1982 that could only run for three hours. It wasn’t until 1999, after decades of work, that the first generation of Spring Drive was born. The breakthrough lay in replacing the collisions of a traditional escapement with an electromagnetic brake acting on a glide wheel. Because this system worked without friction, it produced almost no sound, and the result was the smooth, continuous seconds hand that has become the unmistakable signature of Spring Drive.

The presentation also covered the advances in the modern 9RA-series. These calibers introduced a sensor within the IC to measure internal temperature, improving accuracy in varying conditions. A one-piece center bridge gave the movement greater strength, durability, and shock resistance. The use of twin barrels extended the power reserve to 120 hours, and the redesigned magic lever increased winding efficiency, engaging even with slight movement of the rotor.

As part of the same program, we also saw how Zaratsu polishing is applied to both mechanical and Spring Drive cases. The process is performed entirely by hand, with each artisan learning over years how to hold the case against the polishing wheel at just the right angle. The result is a surface that is distortion-free, reflecting light crisply instead of bending it. Seeing the technique in person highlighted how Grand Seiko applies the same standards of finishing across its collections, regardless of movement type.

What stood out in Shinshu was the balance of technical precision and careful craftsmanship. The facility operated more like a semiconductor plant than a traditional watch workshop, with clean rooms, protective coats, and strict controls to minimize dust and environmental interference. The impression was less about noise and spectacle and more about discipline and focus, the kind of environment where the tiniest tolerances are treated with absolute seriousness.

That philosophy extended beyond Spring Drive. We also learned about Grand Seiko’s 9F quartz. I had always respected the movement, but seeing it explained in such detail reshaped my understanding. It is accurate to within ten seconds per year, compared to the fifteen to twenty seconds per month of a typical quartz watch. The obsession continues even after assembly, with a regulation switch that lets a watchmaker adjust accuracy by half a second per month.

The quartz itself is slow-crafted. A single crystal takes around six months to grow, and from one block, 100,000 oscillators can be cut. While Seiko does sell oscillators to other industries, the ones used in watches are aged and selected specifically for stability. It was clear that quartz, often dismissed elsewhere as disposable, is treated here with the same seriousness as Spring Drive or mechanical. It is a category Grand Seiko approaches with the same philosophy: precision, longevity, and meaning.

North to Iwate: Studio Shizukuishi and the Feel of a Winding Crown

From Nagano we traveled north to Iwate Prefecture, to the Grand Seiko Studio Shizukuishi, home of the brand’s mechanical watchmaking. The building itself felt like a statement. Completed in 2020, the architecture was strikingly modern, with clean lines, open spaces, and walls of glass that framed the surrounding forests and the peaks of Mt. Iwate. It didn’t feel like a factory at all but more like a gallery or cultural center. Every element was designed with intent: the openness emphasized transparency, the views of nature reminded everyone of the brand’s philosophy of time in harmony with the environment, and the light-filled spaces created an atmosphere of calm precision.

Inside, the quiet was remarkable. Instead of the industrial noise one might expect from a watchmaking facility, there was only the faint sound of tools, the occasional hum of machinery, and the soft rhythm of human hands at work. Rows of watchmakers sat at their benches, each one concentrating with an intensity that made it obvious how much training and discipline their craft demands. Many of the artisans here have dedicated decades to perfecting their work, and the studio was designed to honor that lineage. Large viewing windows even allow visitors to watch the process, reinforcing Grand Seiko’s philosophy of openness and respect for craftsmanship.

Our visit included a detailed session on the new 9SA4 manual-wind high-beat movement. The discussion highlighted just how tactile the project was at its core. Movement designer Taro Tanaka said: “The most inspiring aspect for me developing this movement was the tactile sensation when winding the crown by hand.” It was refreshing to hear that for all of Grand Seiko’s technical achievements, something as simple and sensory as the feel of winding could inspire an entire caliber.

That sensation didn’t come easily. Tanaka explained: “We engaged several prototypes, four entirely different structures, each with a distinct feel, and ultimately selected this sliding click…” The team learned through trial and error that tiny parts could determine the overall experience: “The force of the click spring as well as the shape of the click against the wheel… are very important…”

Compared to the 9SA5 automatic, the new movement represented a substantial rework. Roughly forty percent of the caliber had been redesigned and optimized specifically for manual winding. The result was a construction that came in remarkably slim at just 4.15 millimeters in height, thin enough to allow complete watches to stay under the 10-millimeter mark when cased.

Philosophically, it was conceived as both an homage and a forward step. Tanaka said: “We wanted to show our respect towards our original high beat manual winding movement 45GS… but… bring something new… For example, the use of twin barrels for 9SA4.”

For enthusiasts who admire the 9SA5’s chronometric stability, the regulating core will feel familiar. Tanaka explained: “From the main spring to all the gears down to the balance… pretty much exactly the same as 9SA5… Besides that, you can say it’s pretty much all different.” The differences lie in the architecture and finishing choices that make the 9SA4 distinctively manual-wind in feel and proportion.

A lighter moment closed the session when Tanaka clarified Grand Seiko’s internal numbering system: “GMT is six, automatic is five, and manual is four.” It was a reminder that even in a place defined by obsessive detail, the people behind the watches carry an approachable, almost playful pride in their work.

As we wrapped up the seminar, it struck me how much the studio itself reflected what we had just learned. The 9SA4 is a modern reinterpretation of Grand Seiko’s high-beat legacy, and the Shizukuishi Studio feels like a modern reinterpretation of the traditional watchmaking workshop. Both take their cues from history, but neither is afraid to move forward.

Design: Light, Shadow, and Mitate

After days spent in the quieter, less tourist-oriented parts of Japan, the return to Tokyo by bullet train felt almost abrupt. The speed of the Shinkansen brought us back into the energy of the city in a matter of hours, and with it came a change in focus. Where Shinshu and Shizukuishi had been about the mechanics of watchmaking, Tokyo offered a chance to understand how Grand Seiko’s design philosophy brings those mechanics to life.

Back in Tokyo, two conversations with Grand Seiko designers stitched together so much of what I’d seen in the studios. Junichi Kamata, design director of Grand Seiko, described a specifically Japanese way of seeing: “The appreciation of beautiful gradations, not simply… black and white, but shades of gray, is part of the cultural DNA of the Japanese people.” That sensibility is built into the brand’s aesthetic: “Each Grand Seiko watch is designed to represent a unique sparkle based on the interplay of light and shadow.”

Kamata also outlined mitate, suggestion rather than depiction, as a guiding idea for dials that evoke nature without copying it. “Mitate is a suggestion… instead of direct presentation.” Constraints didn’t limit creativity; they sparked it. “Sometimes, when we impose rules, our imagination expands and creativity grows.”

Later in the session, Akira Yoshida, a designer with Grand Seiko, showed how reverence for the archive and exacting documentation inform today’s re-creations. Speaking about the new 45GS re-creation, he said, “We used documents… to consider how to design the recreation.” The case scales for contemporary wrists while keeping the spirit intact: “The recreation size is 2.3 millimeter larger than the original at 38.8 millimeter.”

Back in Tokyo: Seiko Museum Ginza and a Closing Conversation

I ended the trip where Seiko’s story most visibly meets the city: Ginza. At the Seiko Museum Ginza, Director Shuntaro Ishii explained that the museum’s location was intentional. Ginza was where Kintaro Hattori was born, started his business, and established the company, making it the most meaningful place to tell Seiko’s story. Ishii also noted with a smile that the museum benefits from the district’s constant foot traffic, often drawing in curious visitors who stumble upon it while exploring the neighborhood.

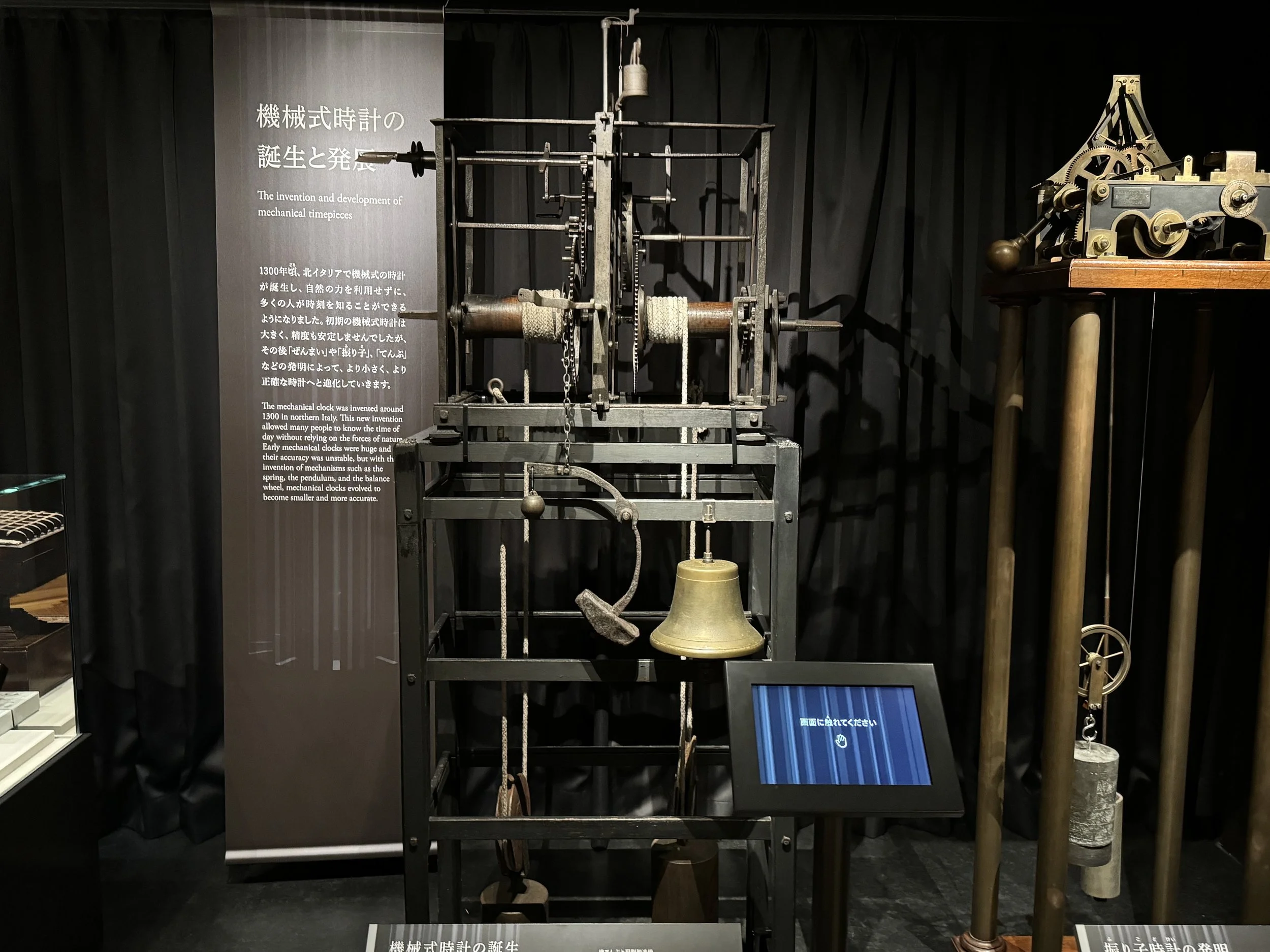

Inside, the museum unfolded vertically, with each floor dedicated to a different chapter of Seiko’s story. The lower levels introduced the broader history of timekeeping, showcasing Japanese seasonal clocks, or wadokei, alongside some of the earliest European clocks ever made. Together they framed the long arc of horology that Seiko would eventually join and transform.

Moving upward, the focus shifted to Seiko’s own beginnings. One display showed the company’s earliest pocket watches, including examples that had been damaged and warped during the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. Seeing them preserved in their imperfect state was striking — they stood as artifacts not just of watchmaking history but of Japan’s resilience. Other cases highlighted the company’s milestones: the world’s first quartz wristwatch, the Seiko Astron, and early examples of Spring Drive models that redefined what a mechanical-electronic hybrid could be.

Higher still was a floor devoted entirely to Grand Seiko. Here, the philosophy of the brand came into focus, with iconic pieces like the Snowflake and Mt. Iwate dials shown alongside the latest innovations. Prototypes of the Kodo Constant Force Tourbillon were also displayed, presented not as a break from tradition but as part of the same lineage. The message was clear: Grand Seiko’s most advanced work is built on the same foundation as its classics.

After the museum, I met with Akio Naito, President of Seiko Watch Corporation. It felt like a fitting culmination to everything I had seen in Shinshu and Shizukuishi. Naito reflected on his own unusual path to leadership, rising from the legal department to CEO, and on the turning points that have defined Grand Seiko’s trajectory. Chief among them was the decision to separate Grand Seiko from Seiko as an independent brand, a move that gave it the clarity and freedom to establish its own global identity.

What stood out most was his insistence that Grand Seiko’s international growth must be grounded in its Japanese character rather than imitating Swiss codes. For him, the brand’s strength comes from the culture it represents—its natural environment, its philosophy of time, and its devotion to craftsmanship. He emphasized that these elements are what differentiate Grand Seiko, not just technically, but spiritually.

Looking forward, he described a brand still guided by its founder’s vision of always being one step ahead, a pursuit embodied in both its most complex creations, like the Kodo Constant-Force Tourbillon, and in its more accessible models. Both, in his view, are united by the same values and the same drive for perfection.

If you would like additional insights, you can read my full interview with Mr. Naito here: Discussing Grand Seiko’s Past and Future with Seiko Watch Corporation President Akio Naito.

As I left the meeting and walked back through Ginza in the evening, the connections felt clear. The museum had tied the brand’s story to the streets around me, and Naito had outlined how Grand Seiko plans to carry that legacy forward. It was consistent with what I had seen throughout the trip: a philosophy of time and craft rooted in Japan, now finding an audience well beyond its borders.

A Few Days to Let It Sink In

When the official program ended, I stayed in Tokyo for a couple more days. I moved from the order and polish of Ginza to the noise and color of Shinjuku. I ate ramen at small counters, visited shrines where the city seemed to quiet for a moment, and let myself process what I had seen. Those unstructured hours turned out to be just as valuable as the tours. They gave me space to connect the precision of Shinshu, the craft traditions of Shizukuishi, and the design culture of Ginza with the rhythms of daily life in Tokyo. I kept coming back to something Chikamata said about how rules can drive creativity, and to Kawauchiya’s idea that the sound and motion of a watch could be a form of art

Conclusion: The Harmony of Means and Ends

Nearly a year later, I still think about this trip often. Certain moments stay with me: hearing the steady rhythm of the Kodo, watching the smooth glide of a Spring Drive seconds hand, seeing how a quartz crystal is grown and tested over months, or feeling the deliberate click of a newly designed winding crown.

What I came to appreciate is how Grand Seiko balances outcomes like accuracy, durability, and beauty with the choices that get them there. The materials, the structures, and the design philosophies are not just technical details, they’re the foundation of the watches themselves.

That approach feels distinctly Japanese. As Junichi Kamata explained, Grand Seiko’s design language grows from the way light and shadow interact. Kawauchiya showed how motion and sound can be part of a watch’s artistry. And in Shinshu, the engineers demonstrated how silence can carry as much weight as precision.

I went to Japan expecting to learn how Grand Seiko makes watches. I came home realizing I had also learned something about how the brand makes meaning, and why its work resonates far beyond Japan.